What does the future have in store for diesel vehicles? Do they have any part to play in transport planning that takes air quality assessment seriously?

In July 2017, the Government’s long-awaited Air Quality Plan was released and came under immediate criticism for failing to heed the requirement from the High Court to take action on air quality ‘by the soonest date possible’. The Plan, which includes £3 billion to deliver the proposed ‘Clean Air Strategy’, was also criticised for leaving too much of the implementation to local authorities. In response, the timetable for implementation of initial plans has been cut from 18 months to 8.

Air quality and diesel vehicles

Poor air quality in the UK is believed to be responsible for a daily death toll of 64. The main culprit is considered to be Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2). NO2 is formed in the air by the incomplete combustion of fossil fuel and can be emitted as primary NO2 or Nitrous oxides (NOx), which then go on to form NO2 in the presence of atmospheric ozone. Whilst both petrol and diesel cars are significant producers of NO2, diesel cars are recognised as the main source of both primary NO2 and NOx.

The first European Directive on vehicle emissions was adopted in 1970 but limited to voluntary compliance. 1992 saw the introduction of the mandatory Euro 1 standard, but this imposed less stringent emission limits for diesel emissions than for petrol vehicles.

Shortly afterwards, a 1993 report published for the Department of the Environment made it clear that it was diesel emissions that posed the greater threat to air quality.

Emission standards for diesel

For almost a quarter of a century since the 1993 report, emission standards have continued to be less stringent for diesel vehicles.

Pre-eminent air quality professional and source reference Dr Clare Holman in her recent article for the Journal of the Institution of Environmental Science points out that:[1]

“At the time, approximately 7 percent of cars were diesel; today they account for nearly 40%.”

[1] Holman, C. (2017) Improving Air Quality: Are vehicle emission limits all smoke and mirrors? Journal of Environmental Science: July 2017. IES, London.

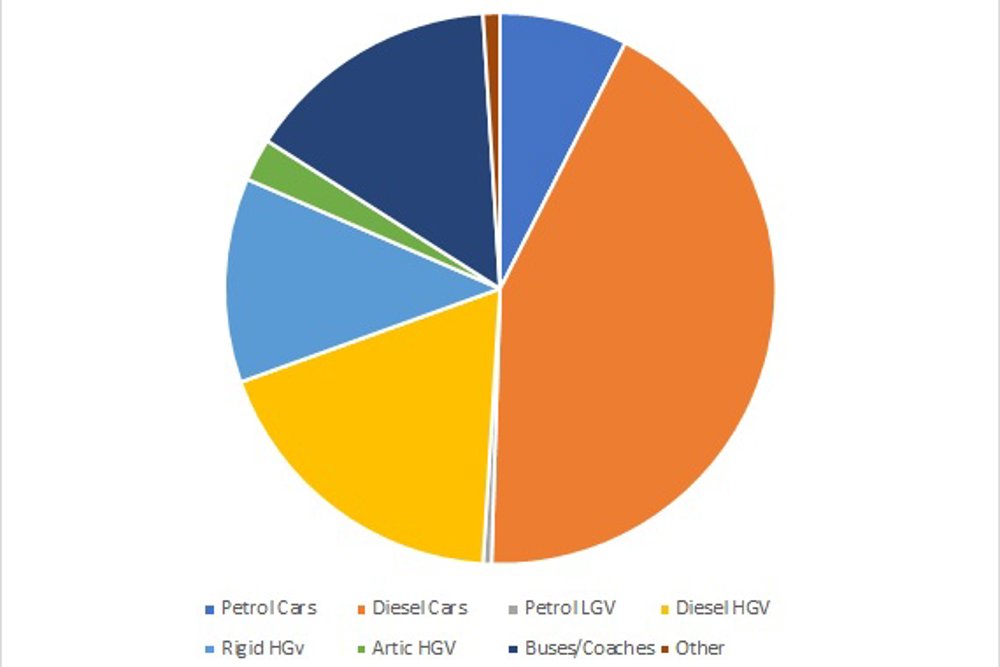

Figure 1. Source-apportionment of NOx emissions from a typical UK Road (based on Defra’s Emission Factor Toolkit V7.0, assuming 5% Heavy Duty Vehicles on an urban road outside of London and at a speed of 50kph) – copy of.

Yet despite increased usage of diesel vehicles and their role in air pollution, the introduction of the Euro emission standards resulted in a significant reduction in NOx concentrations between 1992 and 2003. After this, however, the effects of emission reductions have tailed off.

The diesel discrepancy

Fast forward to 2009 when Gordon Brown’s Government chose, on the advice of EU counterparts, to reduce the excise duty on diesel cars. They also introduced a scrappage scheme to the value of £600 million, aimed in part at supporting the car industry at a time of recession.

The belief that diesel was the ‘greener’ fuel was on the basis that diesel cars appeared to be performing well in terms of emissions, including those for carbon dioxide. However, as time passed, clear anomalies became apparent to air quality professionals as concentrations of pollutants, predicted by models, rarely matched the levels measured.

The discrepancy was acknowledged across the industry and by Defra. Various methods were employed to account for the ‘gap’ between prediction and reality and in 2013, The Highways Agency published a methodology within an Interim Advice Note (IAN).

Numerous air quality consultants devised their own methodologies based upon empirical data and many simply stopped using the future modelling functions altogether; preferring instead to apply current emissions rates to future traffic flows, with no assumption of a future reduction in emissions.

Dissecting the discrepancy

Defra’s 2011 report postulated a range of reasons for the discrepancy, including:

- the ineffectiveness of selective catalytic reduction use in HGVs

- poorer performance under higher engine load in newer Euro classes

- degradation of pollutant reducing catalysts at a faster rate than predicted

Then came the news in September 2015 that Volkswagen had been programming their cars with ‘defeat’ devices, which were set to recognise test conditions and provide emissions several times lower than those emitted in real world driving conditions. It later became clear that other manufacturers were using similar ‘emission control strategies’.

Software programmes such as COPERT,[1] (a software programme currently used world-wide to calculate air pollutant and greenhouse gas emissions from road transport), issued revisions in May 2017. These accounted for the latest findings in real world emissions, but revised factors cannot take account of all the variables that exist. Further answers have emerged, with evidence that Diesel Particulate Filters (DPF), which all diesel cars are required to have by law, are being routinely and discreetly removed during services due to the expense of their replacement.

[1] NOTE: COPERT is coordinated by the European Environment Agency (EEA) within the framework of the activities of the European Topic Centre for Air Pollution and Climate Change Mitigation and the scientific development of the model is managed by the European Commission’s Joint Research Council.

What are the routes to improved air quality?

Air quality campaigners and medical professionals have been calling with a rising sense of urgency, for something to be done. In response, London Mayor Sadiq Khan campaigned hard in the run up to the previous budget for a diesel scrappage scheme to compensate those motorists who bought diesel cars in the belief that they were more environmentally friendly. This was ignored, but his call for a change to the diesel excise duty which is still loaded in favour of diesel cars was heeded this time round in the autumn budget when a rise in diesel car tax was announced.

However, there are other convincing voices in this debate. The president of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Richard Folkson, has said there should not be a rush to scrap diesel cars, given their contribution to reducing carbon emissions. He has asserted that:

“If all new fossil fuel cars were to be solely petrol tomorrow… our average carbon emissions would increase by 16%,"

He has instead called for a rapid introduction of a new testing regime that much more accurately reflects driver behaviour.

This view is backed by air quality consultants’ findings on real world emissions conducted by several organisations. They cite that not only is there a great deal of variability between different diesel vehicles and their various emission control strategies, but that emissions can vary significantly according to factors such as driving conditions and temperature.

In addition, the RAC question the efficacy of scrappage. Their analysis points to a cost of £800 million resulting in a 3.2% cut in NOx emissions from diesel vehicles.

What choices do we have?

In February 2017, Transport Secretary Chris Grayling said that: “We’re going to have to really migrate our car fleet, and our vehicle fleet more generally, to cleaner technology.”

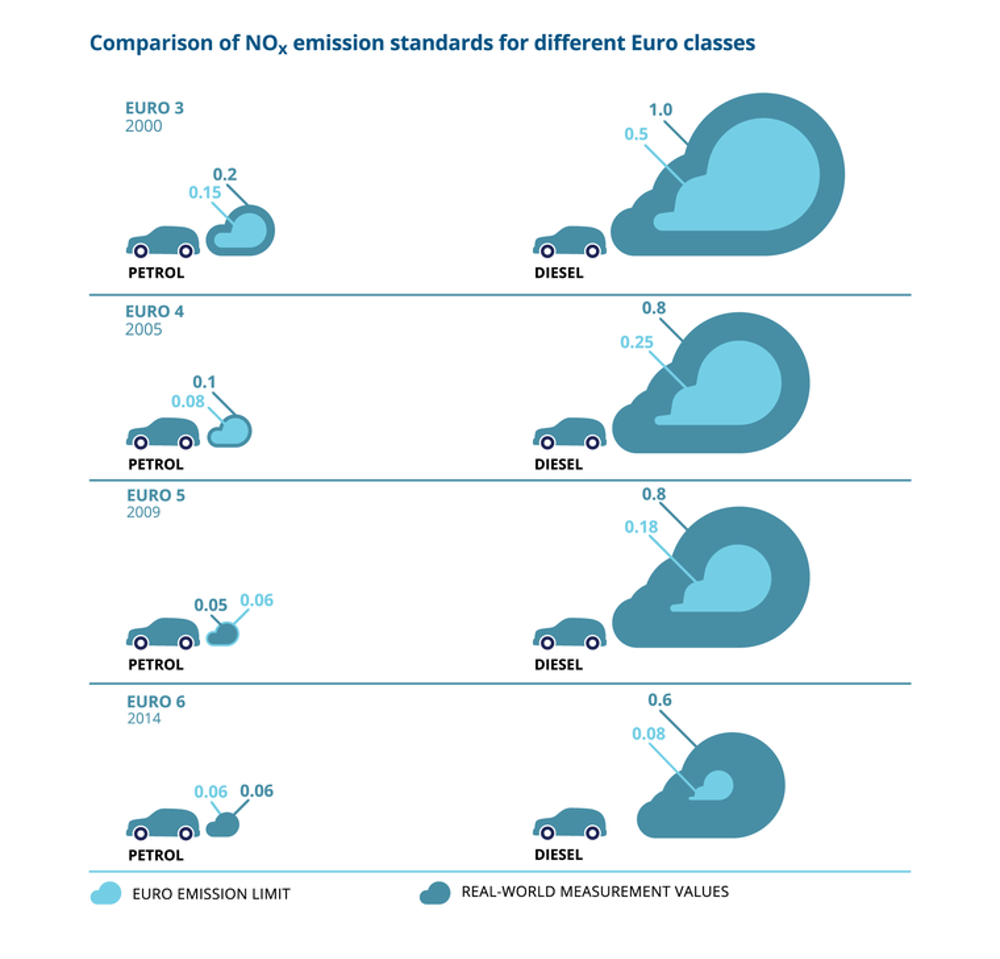

It was assumed at the time that this was reference to a move towards the new Euro 6 generation of vehicles. Unfortunately, studies demonstrate that whilst Euro 6 diesel cars do emit significantly less NOx than the previous Euro 5 or 4 vehicles, they still emit significantly more than the emission standard.

Note: Nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions (in g/km)

Adapted from: ICCT, 2014a; Emisia 2015

Figure 2: Comparison of NOx Emissions and Standards for Different Euro Classes [Source: European Environmental Agency]

However, the new Air Quality Plan appears to include a pledge to halt the production of new petrol and diesel cars by 2040, presumably on the assumption that new, cleaner technologies will have fully infiltrated the vehicle fleet by this time.

Plans unveiled by Sadiq Khan in June 2017 include measures to go beyond bringing forward and expanding the planned Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ)m and the inclusion of a ‘Toxic’ or T Charge which has been applicable to older cars since October. The draft strategy also contains ‘pay-as-you-drive’ road pricing, which would charge according to vehicle type, emissions and location.

So, what is the best way to tackle air pollution and in particular, diesel emissions?

Whilst direction is still sought from central Government, the latest Air Quality Plan appears to indicate that local authorities are expected to develop their own costed strategies. A difficulty with this approach is that it can be seen to sit in conflict to their LAQM duties under the Environment Act (1995) to assesses and control air quality in relation to local population exposure.

In the meantime, Wales has moved away from Local Air Quality Management altogether and towards the adoption of methods set out in the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015. Welsh Authorities it seems, are now seeking their own more holistic approach with longer term solutions in line with existing planning, permitting and nuisance regimes. Scotland, on the other hand, is progressing independently with it’s national ‘Cleaner Air for Scotland’ policy, and its ambitious aim “to have the best air quality in Europe”.

It would seem therefore, that even with the emergence of the Government’s new Air Quality Plan, and the slow recognition of the dire need to control emissions from both petrol and diesel vehicles, the route to clean air in the UK is a divergent and convoluted path, which is still very far from clear.

|

SPECIFIC THANKS TO Jack Pease: Air Quality Bulletin Dr Ben Marner: Technical Director – Air Quality Consultants, Member - Defra Air Quality Expert Group Dr Clare Holman: Director - Brook Cottage Consultants, Chair - Institute Air Quality Managers For the detailed air quality work referenced throughout this blog. |